Listening to the voice of that most estimable African tenor Nyboma Mwan’dido, heard in my previous two postings, it isn’t hard to imagine him as a good natured, earnest type, natty in beret and vest. The band that he fronted, L’Orchestre de Kamalé (later Kamalé Dynamiques du Zaîre), played sweet and hot by turns, lolling in the sun one moment, then challenging the posted speed limit in the next. Most importantly, both Nyboma and his band were purveyors of roots music in its best sense, rough-hewn and sophisticated in one go.

Not so many years after Pepe, the subject of our last post, we find Nyboma a titular member of Les Quatre Étoiles, a supergroup (to Westerners of a certain vintage, an ugly word, but unavoidable here) comprised of rumba Congolaise veterans; its other members were guitarist Syran M’benza, Kamalé bassist Bopol Mansiamina, vocalist Wuta Mayi. Their second album, Dance, preserves for all time one of those ridge-of-the-roof moments, when technocratic impulses began to carry the day, altering the intrinsic character of music.

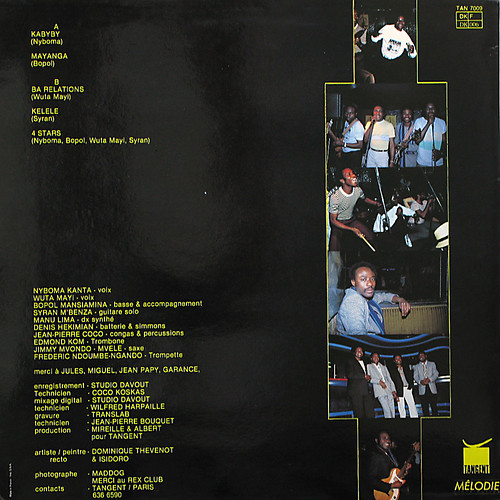

The Four Stars are pictured on the cover of Dance, celebrating in a Parisian nightclub. Tricked out in suits, each member has become a sapeur, being the term used by Congolese fans to denote a musician with marked clothes horse tendencies. Papa Wemba has served as the poster boy for sapeurs throughout his career, though surprisingly this does little to enhance my enjoyment of his voice. My sole concert experience of Wemba convinced me that he was a sour-natured pimp, macking on his lady singers while fronting a so-so band. Armani will only carry a fella so far...

Elegance in comportment extends to the Four Stars' songs (four of which are heard here; I deleted the eponymous jam ending the album). They dispense with the slower, Latin-flavored intro that had characterized soukous prior to the mid-‘80s. The seben, with its relentless beats and pell-mell tempo, is the sum and substance of Dance. Synthetic facsimiles all but supplant the horn players of yore, though the brass arrangements remain unmistakably Congolese; vivacious and sly, their phrases twist upwards like sumi-e calligraphy rendered in cigarette smoke. Unfortunately, I suspect this album is among the early all-digital recordings (Ry Cooder’s Bop Til You Drop, released from six years earlier in 1979, being the first DDD pop record), which may explain Dance's occasionally harsh veneer.

Add to an already binary scenario that bane of early MTV music, the Linn Drum with its unmistakably fizzy timbre, and the record might have been remembered as one more high-tech travesty from the ‘80s. That it has aged well speaks to the human components of Dance, said humans being of high quality indeed. The songs are consistently good, with all Four Stars in excellent voice. Then there is Syran M’benza’s guitar, a thing of beauty. A zaftig African music maven of my acquaintance once told me that she wanted to live in Syran’s guitar amp. Unless Syran used a Marshall cabinet (doubtful), it never would have worked, yet I could understand her ambition. The guitarist's liquid tone plays as an African counterpart to that of either George Benson or Benson’s Jamaican acolyte, Ernest Ranglin.

Years down the track, having wearied of their existence as journeymen on the world music circuit, most of Les Quatre Étoiles regrouped with renewed energy as the all-acoustic Kékélé. Their two recent albums on the Stern’s label, Congo Life and Rumba Congo, both rank as transcendent marvels, their songs articulating horizontal urges in the best hedonist tradition.

DANCE (@160)

Comments

mangorio