In previous NCIP posts, something like evangelism carried the day. I was a man with a mission, hell-bent to rope you on my obsessions of the week/month/season, a mission that I plan to continue. Today's entry, however, requires disclosure; either it will hold appeal...or it won't. The sound of the Indian double reed instrument known as the shehnai is not for everyone. Its timbre a hybrid of oboe and soprano saxophone, the shehnai nestles comfortably alongside such particular tastes as uni, the films of Yasujiro Ozu, the chile that they used to serve at Motor City Dragway, the best episodes of Captain Beefheart's career, Krazy Kat cartoons, Lord Buckley's monologues...you probably see what I'm getting at here. There's really no fence-sitting to be done. First, listeners should be willing to give over to the spare, ascetic form of North Indian classical music. Then, assuming an affection for the sculpture made from cigarette smoke that is a raga, we can begin to consider the version according to Ustad Bismillah Khan. At which point it gets serious.

My introduction to the piercing and plaintive tone of Bismillah Khan's shehnai happened in one of my favorite settings, a bootleg restaurant. Perhaps you've enjoyed something similar: There's no certificate of inspection on the wall, because the city isn't aware of the existence of the eatery in question. I had attended a concert at Toronto's Music Gallery ("No tunes allowed" read the sign over the entrance) in the company of a Toronto native whom, a few years before, I had bullied into becoming my friend. After the concert, the promise of an amazing meal lured us upstairs. We entered a loft of defining bohemian mien above the gallery. I recall the ambience as being the brighter side of stygian. We stumbled over other diners in the gloom. Throw pillows sufficed for seating. Discussion and smoke wafted about the space at knee-cap height. Indian food was being prepared and the air itself was nearly saffron-colored as a result. And, as is often the case with off-the-books dining (for whatever reason), lots of lp sleeves were scattered about. Nearly all of these held Indian albums. I picked up a record jacket that felt light to the touch and, of course, its mesmerizing contents issued from the house system in that moment. I was hearing Bismillah Khan for the first time and, yes, I wound up in love with the sound of shehnai. Not immediately, as I'll admit to being enveloped and audibly tasered by what my fellow Detroiters might recognize as the weirdness of it all. After ten or so minutes the shehnai player had moved out of the drifting, free-meter portion of the raga known as alap and into the rhythmic movements that followed. I was pole-axed with happiness by this point in the proceedings.

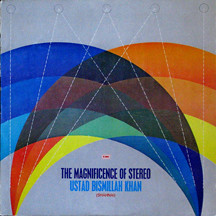

The Magnificence Of Stereo was the album that I heard during that unforgettable meal (involving as it did celestial channa masala, served by local free spirit Gordon W). The sleeve that I tried to read in the dimly-lit loft condensed, within a 12" square, everything that I've come to love about Indian music: Hyper-effusive praise for the author of the recording, the liner notes wrought in fantastically purple prose; kooky graphics, in this instance explaining the multi-dimensionality of the recording you are about to hear; and, of course, a title that may have little or nothing at all to do with the centuries-old stories embedded wordlessly within the ragas comprising The Magnificence Of Stereo. A very good film writer from New York, the Voice's J. Hoberman, once described the beyond-Busby Berkeley song-and-dance routines of Bollywood cinema as "MTV for the very, very stoned." Would that I could summarize the otherworldly character of Bismillah Khan's music, especially today's slice of same, so neatly.

I only heard Bismillah Khan in concert once. He appeared at Manhattan's Town Hall during the '80s. He was already very old, that much was evident. I knew within moments of sighting him that this would be his final American tour. He played beautifully, though his jaw muscles and embouchure weren't quite up to the hailstorm of pointillist phrasing that had once been his signature in sound. It didn't matter. I had paid an unholy sum to sit in the back row of the balcony. Around me was India in microcosm: Everyone talked throughout the performance; everyone spoke a different dialect; nearly all of the balcony was involved in varying degrees of dispute, with hissing and scolding galore; babies cried; dinner was being eaten from a multitude of plastic containers (the curries smelled fantastic and drove me to distraction). The presenters of this event took every opportunity to interrupt the set, laying a funeral home's allotment of flowers on the stage and seizing the mic whenever Bismillah Khan took a break, the better to sing the praises of their organization.

None of this, unbelievably, affected my enjoyment of the snowy-haired fellow seated cross-legged at stage center. I was sharing a (huge) room with Bismillah Khan & party and I was so happy. I could have heard more of his shehnai, and far less of my neighbors and less of the endlessly tiresome minions of the concern that staged the show and less even of the racktastic hostess from the Namaste America TV show, who introduced Bismillah Khan (yes, even she wore out her welcome in short order). The concert was still the stuff of transport, even with annoyances factored in. Stanley Booth said it best, describing his own, nearly fatal proximity to the Rolling Stones on their 1969 tour: At least I got to hear the band play.

Ustad Bismillah Khan died in 2006. He was extremely old when he died, older than Judy Garland looked when she bought the farm; in his deathbed photographs, he resembled nothing so much as a twig of cardamom nestled within white sheets. His was an enviable lot in many respects. His forebearers played shehnai, and he, in turn, did so too. As the person responsible for elevating his instrument into the classical canon — previously, it had only been deemed appropriate for wedding music and for greeting pilgrims approaching a temple — Bismillah Khan was considered the ne plus ultra of shehnai players throughout his life, never less than innovative and deeply soulful into the bargain. His shadow arched over so many musicians following in his wake. John Coltrane was smitten with his sound, as later were the minimalist composers La Monte Young and Terry Riley, during their respective spells as saxophonists. Bismillah Khan died where he'd lived his entire life, in Varanasi, on the banks of the Ganges.

Nearly every obituary that I read last year mentioned Bismillah Khan's favorite mode of transportation: a bicycle rickshaw. None of the obituaries that I read last year mentioned the quality that seemed literally as plain as Bismillah Khan's face: the expression that he wore in so many of the photographs taken of him, an expression that telegraphed a degree of wry amusement and perhaps even watchfulness of a worldly sort (those acquainted with the arcana of the Stooges' legend will recognize this as TV Eye). He was a musician, after all, and had a small army of grandchildren at the time of his passing, so maybe I'm not simply reading too much into this faintly picaresque aspect of his visage. It wears well on a musician steeped in liturgical repertoire.

Incidentally, the accomplice guiding me towards the Indian meal in Toronto was Michael Brook, the guitarist and producer who, not so much later, was to garner well-deserved renown of his own. (Most recently, Michael scored Sean Penn's newest film Into The Wild, due in theaters immediately.) Two decades and some down the line from that meal, Michael and his missus Julie recently produced a son, Felix, who thoughtfully turned up on my own birthday (Aug. 27th). This post's for you, Felix.

THE MAGNIFICENCE OF STEREO

Comments

I just checked, & the link to another UBK album I posted is still working:

http://skafunkrastapunk.com/forum/viewtopic.php?p=172262&highlight=bismillah#172262

rs:

http://anonym.to/?http%3A%2F%2Frapidshare.com%2Ffiles%2F11332952%2FUBKall.zip

Ah yes, the Shehnai ... I have heard it - the instrument... 'live'...I'm bothered because I can't remember if it was in Pushkar or in Varanasi.

Please allow me to share this with you all:

The plaintive shenai, a double-reed chanter most closely resembling the Western oboe, was brought out of Indian temples by the legendary Bismillah Khan and introduced into the Hindustani classical canon. This album, recorded in North India by John Levy and initially issued by the French Tangent label, affords the curious glimpse of the instrument in its original context. Anyone who has attended a recital by Khan or Ali Ahmed Hussain knows that the shehnai projects as no other woodwind can.

Visiting the temples of Ajmer and Mundra one learns why: it was meant to be played in the open, in galleries above gateways or in courtyards. Much of this disc, now enhanced by CD mastering, contains what poultrymen might regard as free-range classical music. As a change of pace, a devotional song based on “Raga Darbari Kanada”, a late night raga, is offered with both dholak (spike fiddle) and shehnai accompaniment, a rare event in itself. The acoustic context is a fascinating sidebar to any field recording, especially so for this set, as the report of the taut-skinned tabal kettle drum skitters around the courtyard walls of the Ajmer temple. Also included is a rare mashak bagpipe solo.

Recorded live between 1952 and 1962.

Music from the Shrines of Ajmer and Mundra

1.: Classical Naubat Shahn a 'i (Mundra)

2.: Classical Naubat Ahahn a'i (Ajmer)

3.: Kacchi Kafi

4.: Popular Naubat Shahn a'i (Jabbalpur)

5.: Mahak (Indian Bagpipes)

6.: Popular Naubat Shahn a'i (Bhopal)

http://rapidshare.com/files/139032247/MFTSOAjmer_and_Mundra.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139081032/MFTSOAjmer_and_Mundra.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139123932/MFTSOAjmer_and_Mundra.part3.rar

The files are in 'flac' lossless format so they weigh in at approx 240 mbs in total...but well worth the trouble.

cheers and thanks again.

Please ReUp,..... megaupload please!!!

Or does anyone have a torrent link!?!

Please reupload,...... eagerly waiting to hear the same!!!!!!

It's extinct online already,..... Please reupload it/ torrentify it otherwise,.......

Eagerly waiting for a fresh Upload!!!!!